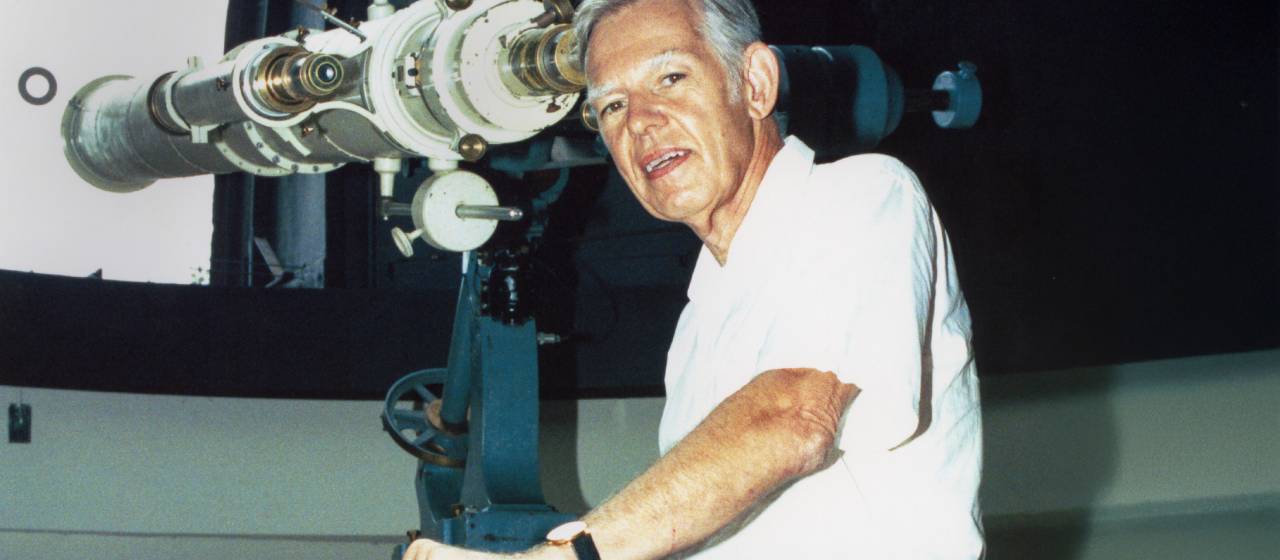

Russell Kulsrud, one of the last survivors of Project Matterhorn, dies at 97

Russell Kulsrud, Princeton professor of astrophysical sciences, emeritus, died on Sept. 23 at the age of 97.

“Russell was one of the people that established the reputation of Princeton Plasma Physics Lab as the place to do plasma physics in the world,” said Sir Steven Cowley, director of the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory and a professor of astrophysical sciences at Princeton University, who was Kulsrud’s mentee and completed his Ph.D. at Princeton in 1985.

Among his many contributions to plasma physics and astrophysics, Kulsrud expanded scientists’ understanding of the universe’s plasma, including the dynamo mechanism responsible for generating magnetic fields in space and the process of magnetic reconnection, the explosive breaking and rejoining of magnetic field lines that transfers enormous amounts of energy from magnetic fields to plasma.

In 1954, Kulsrud joined Project Matterhorn S, a highly classified fusion research project under the leadership of Lyman Spitzer, which would soon evolve into the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL). The Matterhorn physicists “established much of the basis of plasma theory, magnetized plasma theory, and fusion theory,” Cowley said.

“Plasma physics basically didn’t exist until Spitzer formed that group,” he said. “There were just a handful of papers about plasmas before then, so they had to invent the field at the same time as try and solve fusion. Russell, and Ira Bernstein, who was head of applied physics at Yale for many years, and Martin Kruskal, who was here at Princeton, and Ed Frieman, who was head of the Scripps Institute for many years — it was an all-star group, and Russell was one of the leaders. In 1958, they published a paper about the stability of plasmas, which is probably the most cited paper in plasma physics. It’s called the Energy Principle Paper, and it was Bernstein, Frieman, Kruskal and Kulsrud. That paper was hugely influential and remains one of the classics to this day. Those four were just astoundingly good.”

Kulsrud was the last survivor of “those four,” and he appears to be the last of the Matterhorn S physicists, said Cowley. (Kenneth Ford, a Matterhorn B scientist and prolific author, is 99 and living in Pennsylvania.)

“A towering figure” at Matterhorn and PPPL

“Russell Kulsrud was one of the greatest scientists of our age, a towering figure in theoretical plasma physics and astrophysics,” said Dmitri Uzdensky, a 1998 Ph.D. graduate of Princeton who is now a professor and the director of the Center for Integrated Plasma Studies at the University of Colorado-Boulder. “His many seminal, truly foundational contributions have guided the development of theoretical thought in plasma physics and have influenced — and I am sure will continue to influence for decades to come! — broad swaths of research in thermonuclear fusion, space physics and plasma astrophysics.”

Born April 10, 1928, in Lindsborg, Kansas, Kulsrud attended the University of Maryland-College Park for his undergraduate degree (B.A., 1949) and then the University of Chicago for graduate school, completing his M.S. in 1952 and his Ph.D. in 1954. At Chicago, Kulsrud studied under legendary physicist Enrico Fermi, and his doctoral advisers were the renowned Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar and Bengt Strömgren.

Immediately after completing his Ph.D., Kulsrud joined Project Matterhorn S — S for stellarator, a fusion energy control device, to distinguish it from Matterhorn B, which was developing nuclear bombs.

At PPPL, Kulsrud was promoted from “physicist” to “senior research associate” in 1959, and by 1964 he was named the head of the Theoretical Section of Project Matterhorn. (After the bomb project closed in the 1950s, Matterhorn dropped the S.)

Kulsrud began teaching Princeton University courses in 1960, and in 1989 he formally joined the University faculty as a full professor. In 1993, Kulsrud received the prestigious James Clerk Maxwell Prize for Plasma Physics from the American Physical Society. His citation honored “his pioneering contributions to basic plasma theory, to the physics of magnetically confined plasmas, and to plasma astrophysics.”

Other than a one-year sojourn at Yale (1966-67), Kulsrud spent his entire career at Princeton.

He transferred to emeritus status in July 1999, but he retained his status as a research scholar until July 2024. He published “Plasma Physics for Astrophysics” with Princeton University Press in 2004. He advised graduate students and postdoctoral fellows throughout his career.

“He gave me his time”

Kulsrud loved working directly at the blackboard, chalk in hand, said several of his former students, including Cowley. “Starting in September 1982 and for the next three years, I spent three hours a day with him, working on the blackboard,” recalled Cowley. “What’s the most valuable thing somebody can give you? Their time. He gave me his time in a quantity that very, very few Ph.D. advisers ever give their students. I always say that if you do physics to win prizes, you’re not going to win prizes. You have to do it because you just love the process, every day. That’s why Russell continued to do physics until he was into his 90s, because it was more fun than anything else.” Cowley became close with the whole Kulsrud family, spending Christmases with them for years afterward.

Kulsrud’s first Ph.D. advisee was Catherine Cesarsky, then a graduate student at Harvard and a senior scientific adviser for the French Atomic Energy Commission.

“Although I had an official adviser at Harvard, Russell was my true mentor,” Cesarsky said. “We had an exhilarating time intellectually. There was so much for me to learn from him. I deeply admired his insight and mastery of the problems we discussed, but I also challenged him constantly — making him think hard, or so he said. I remember that our discussions were so intense that he often had to pause for a coffee break!”

Another of Kulsrud’s early students was Ellen Zweibel, a 1977 Ph.D. graduate of Princeton who is now the W. L. Kraushaar Professor of Astronomy and Physics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“Russell had a unique approach which combined mathematics and physics at the highest levels,” Zweibel said. “His work was elegant, and he had a gift for identifying problems and asking questions that exposed critical physics issues.”

“His academic progeny includes many of today’s scientific leaders in both fusion plasma physics and astrophysics,” said Uzdensky, who worked with Kulsrud on magnetic reconnection at PPPL in the 1990s and continued to collaborate with him for years afterward.

Uzdensky added: “I warmly cherish my memories of the many hours we spent arguing about magnetic reconnection at the blackboard in his office, his patience and human kindness, his jokes, his exceptional scientific honesty, and his sincere and contagious intellectual curiosity that has always been his primary driving force.”

“With his keen intellect and remarkable physical intuition Russell would address the heart of a problem and figure out how to solve it,” recalled Allen Adler, a 1978 Ph.D. whose career included vice presidencies at HRL Laboratories and Boeing. “In addition to his scientific talent, Russell was a very kind person. He taught me many valuable lessons that served me well in life and in my professional career.”

Masayuki Ono came to Princeton as a graduate student in 1973 and has remained with PPPL ever since. He is now a principal research physicist with the National Spherical Torus Experiment. “Russell was an amazing person who was so sweet and disarming yet so smart and knowledgeable,” Ono said. “I truly enjoyed his lectures, since Russell approached any plasma physics problems from the very basics and built them up with logical steps. I deeply appreciate Russell for the precious time he spent with me, which positively impacted my research career. Russell is also my role model when I interact with my own students and research colleagues. While Russell is no longer with us, his legacy will live on.”

Mentoring generations of astrophysics leaders

Michael Shull, who completed his physics Ph.D. in 1976, described Kulsrud’s class “Plasma Astrophysics” as a highlight of his time at Princeton.

“Looking back on those years in the 1970s, I realize that they opened a view of the richness of physical studies of the universe,” said Shull, who is now a professor of astrophysics and planetary sciences at the University of Colorado-Boulder. “His lectures and his book provided powerful tools for modelingand understanding phenomena in the solar wind, supernova explosions, interstellar gas, and the intergalactic medium that contains most of the ordinary matter in the universe.”

Shull added: “Russ Kulsrud was also a kind, friendly and gentle man who exuded the pleasure of learning about these processes.”

“He has played a formative role in my life, and the lives of so many others,” said Alexander Schekochihin, a 2001 Ph.D. graduate who is now a professor of theoretical physics at Oxford University. He described Kulsrud as one of “the most prolific and intellectually diverse” scientists in the field, “due not only to the depth and creativity of his physics but also to the way he was with all of us: a kind and truly liberal man, generous in sharing his time, his energy and his ideas, but also welcoming to all manner of different ways of thinking. This feels like the end of an era in our field.”

“Russell was kind, compassionate and generous of spirit,” said Haldan Neal Cohn, a 1979 Ph.D. who is now an emeritus professor of astronomy at the University of Indiana-Bloomington. “He viewed our work together, when I was a graduate student, as a collaboration and treated me as a research colleague.” He said that Kulsrud “generously” adapted code that he had written for fusion plasma simulation into a tool that Cohn could use to study star clusters.

“While this subject was considered highly speculative at the time, and well outside of the realm of plasma astrophysics, Russell was clearly delighted to be working on it with me,” Cohn said. “Our work together led to a paper that we published that continues to be regularly cited.”

Kulsrud mentored generations of physicists, including young scientists who joined PPPL without formally studying under him. One of those, Masaaki Yamada, is the principal investigator of the PPPL Magnetic Reconnection Experiment.

“Russell Kulsrud was not only a lifelong mentor to me but also an invaluable friend and constant companion in my research endeavors,” said Yamada. “He approached our work from a theoretical standpoint, while I contributed as an experimentalist, and our constant debates and discussions were invaluable; I learned so much from him.”

Yamada studies the separation and explosive reconnecting of magnetic field lines in plasma — the trigger for auroras, solar flares and geomagnetic storms that can disrupt power grids and GPS signals on Earth.

“I often reflect on what made him so captivating, and I believe it was not only his deep insights into physics but also his gentle and kind demeanor toward everyone — students and colleagues alike,” said Yamada. “He was a compelling and charismatic individual of great stature. I deeply miss him.”

Hantao Ji, a professor of astrophysics at Princeton, is another leader in magnetic reconnection. “I had the privilege of working closely with Russell since my arrival in Princeton 30 years ago, as a postdoc in 1995,” Ji said. “One thing that I remember vividly is that he would ask the same, seemingly dumb, question, over and over again, until everyone realized that the question was actually quite deep but had been ignored until then. Even though he wasn’t a mentor or an adviser of mine in any formal way, he had a profound influence on my life.”

Kulsrud is survived by his daughter, Pamela Corey, and son-in-law, Troy Corey. He was predeceased six months ago by his wife Helene, a pioneering computer scientist, and their children, Suzanne Allison Gammon in 1951 and Peter Clifford Kulsrud in 2009. Donations to honor Kulsrud may be made to the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research.

View or share comments on a memorial page intended to honor Kulsrud’s life and legacy.

Latest Princeton News

- Prospect House spaces dedicated for ‘exemplary individuals’ who helped to shape the University and the world

- 'Many Minds, Many Stripes' conference celebrates Princeton's community of graduate alumni

- Michael Skinnider wins 2025 Packard Foundation Fellowship

- A ‘town square for the arts and humanities’: The new Princeton University Art Museum shares opening details

- The ‘Many Minds, Many Stripes’ conference celebrating Graduate School alumni is underway on campus

- Society of Fellows in the Liberal Arts welcomes new scholars