Edmund White, professor of creative writing and ‘iconic gay writer of the 20th and 21st centuries,’ dies at 85

Edmund White, professor of creative writing in the Lewis Center for the Arts, emeritus, died at his home in Manhattan on June 3. He was 85.

White, who joined Princeton’s faculty in 1999 and transferred to emeritus status in 2018, was the author of more than 30 books — fiction, biography, nonfiction, memoir — nearly all of which center on themes of the gay experience.

“Edmund White was one of the most influential and groundbreaking figures in gay literature,” said Yiyun Li, professor of creative writing in the Lewis Center for the Arts and director of the Program in Creative Writing. “He approached his subjects, both in his fiction and in his nonfiction, unapologetically, with utter candidness, joy and playfulness. His work has made space where there was none before him, and this space has allowed the younger generations of gay writers to exist and thrive.”

As a colleague and friend, “he had a wicked sense of humor — sharp-eyed but never mean-spirited,” she said. “He was exceedingly kind and generous, one of the most knowledgeable people. It was an endless joy to hear him talk about literature, history, music, art, or any subject. He has left a vacancy in many friends' lives, an absence that will remain acute.”

Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Paul Muldoon, who was director of the creative writing program when White was hired, called White “the iconic gay writer of the 20th and 21st centuries.”

“Like all icons he was an iconoclast, revered because of his very irreverence,” said Muldoon, the Howard G.B. Clark '21 University Professor in the Humanities and professor of creative writing in the Lewis Center for the Arts. “His presence was an absolute delight.”

“His students learned from him, of course, but he was exemplary to all of us for his wonderful combination of graciousness and grittiness, immense learning and legerdemain that he brought not only to his writing but his day-to-day life,” Muldoon said. “The one thing we couldn’t begin to replicate was his droll wit. That was all his own.”

In New York and Paris, chronicling gay life with candor

White was born in Cincinnati in 1940. His parents, a chemical engineer and a school psychologist, divorced when he was seven. He earned his bachelor’s in Chinese at the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor in 1962, then moved to New York, where he worked as an editor and writer, first at Time-Life Books, then Newsweek, The Saturday Review and Horizon magazine. He moved to Paris in 1983 for a one-year Guggenheim fellowship and stayed, writing and editing from there until his tenure at Princeton began.

White chronicled his sexual awakening, decades of love affairs and social exploits as a gay writer, in New York and Paris, in four memoirs: “My Lives” (2005), “City Boy” (2009); “Inside a Pearl: My Years in Paris” (2014), and most recently, “The Loves of My Life: A Sex Memoir,” published earlier this year.

A fifth memoir, “The Unpunished Vice: A Life of Reading” (2018), is described by the publisher, Bloomsbury, as “a compendium of all the ways reading has shaped White's life and work.”

His novels also animate gay life across decades, beginning in the 1960s. Many, like the trilogy “A Boy’s Own Story” (1982), “The Beautiful Room Is Empty” (1988) and “The Farewell Symphony” (1997), are semiautobiographical.

His first novel, “Forgetting Elena,” was published in 1973, garnering his first and favorite accolade, from Vladimir Nabokov, who called the book “marvelous.” White adored Nabokov’s “Lolita,” and held it up as a high bar for his own aspirations as a writer. According to a bio written by a colleague when White transitioned to emeritus status, White said: “I instantly loved this book because it was outrageously funny, sexy, and passionate and, finally, gorgeously written.”

White’s historical fiction includes “Fanny; A Fiction” (2003) and “Hotel de Dream: A New York Novel” (2007). In 2006, he wrote the play “Terre Haute,” a fictional encounter between author Gore Vidal and the Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh. He also wrote hundreds of book reviews for The New York Times Book Review, The Washington Post Book World, The Nation and Vogue, and The London Review of Books, Times Literary Supplement and The Sunday Times in the United Kingdom, among others.

White was also an activist and advocate, particularly during the AIDS crisis. He cofounded Gay Men’s Health Crisis in 1982 and served as its first president. When he moved to Paris the following year, he helped found a similar organization, AIDES. Soon after, he tested positive for HIV, which added another distinctive facet to his point of view as a writer. He lost many friends to AIDS, including four members of the Violet Quill, a gay writers group he belonged to in New York, among them his editor Bill Whitehead, a 1965 Princeton graduate.

White lived in Paris until 1998, writing his biography of French playwright Jean Genet (“Genet: A Biography,” 1993), which earned the National Book Critics Circle Award; “Our Paris: Sketches from Memory" (1994), co-written with French architect and illustrator Hubert Sorin; “The Flâneur: A Stroll Through the Paradoxes of Paris” (2000), his love letter to the city of Paris; “The Married Man” (2000), a fictionalized account of his relationship with Sorin; and nonfiction works about Marcel Proust and Arthur Rimbaud. In 1993, he was named an Officier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French government.

Giving students a moment to “explore their own imagination”

In the classroom White left an indelible mark on future literary voices and lifelong readers, alike. His writing seminars were the first formal introduction to fiction writing for hundreds of Princeton students. He served as director of the Program in Creative Writing from 2002 to 2006.

In a University homepage story in 2006, he acknowledged that not all his students wanted to become writers, but he still felt their decision to take his seminars was important. “What they really want is a moment in their Princeton career when they can express themselves and explore their own imagination,” he said.

Some, of course, did become professional writers. Christopher Beha, a novelist and former editor of Harper’s Magazine, graduated from Princeton in 2002 and took several classes with White.

“He was worldly and sophisticated without being cynical, erudite without being pretentious. He talked about literature with great passion and seriousness, but he didn't take himself seriously,” Beha said. “We all adored him and loved his writing but we were drawn above all to his way of being a writer in the world.”

Beha was diagnosed with lymphoma his senior year and underwent chemotherapy. He shaved his head and worried what others would think. White set him at ease immediately. “He exclaimed how lucky I was to have such a well-shaped skull. ‘You look like a French intellectual!’ he gushed. This from a man who'd known Foucault personally. He'd said precisely the thing I needed to hear. I got better. And I've shaved my head ever since.” The two remained friends until White’s death.

Laura Preston, a 2013 graduate and New York City-based freelance writer whose work has appeared in The New Yorker and n+1, said White loved all of his students’ writing, which both charmed and encouraged them.

“He loved our plotless compositions, our dream sequences, our car crashes, our sermons, and our highly technical explanations of outer space guns,” she said. “The course's tacit injunction became ‘make Edmund laugh.’ In trying to make Edmund laugh, our writing became bolder and more honest. I sometimes wondered if, in his jolly appreciation of our worst efforts, he was challenging us to be sponge-like, to receive more, and to love more.”

Years later, Preston visited White in his West Village apartment, where she saw more evidence of his passion for living a well-read life. “His bookshelves were overabundant and dangerous, a structural miracle, with books crammed between the tops of the shelves and the ceiling like one of those hand-built stone walls in New England. These shelves were the physical evidence of his appetite for literature, personalities and the visible world — which is to say they were a monument to his love.”

Some of White’s students returned to campus in 2013 for “Every Voice,” Princeton’s first conference celebrating its LGBTQ+ alumni community — and rose to their feet for a standing ovation following White’s keynote address.

White was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, was named as state author of New York in 2016, and received the PEN/Saul Bellow Award for Achievement in American Fiction and the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters from the National Book Foundation, among other honors and awards.

He is survived by his husband, Michael Carroll, and a sister, Margaret.

View or share comments on a memorial page intended to honor White’s life and legacy.

Latest Princeton News

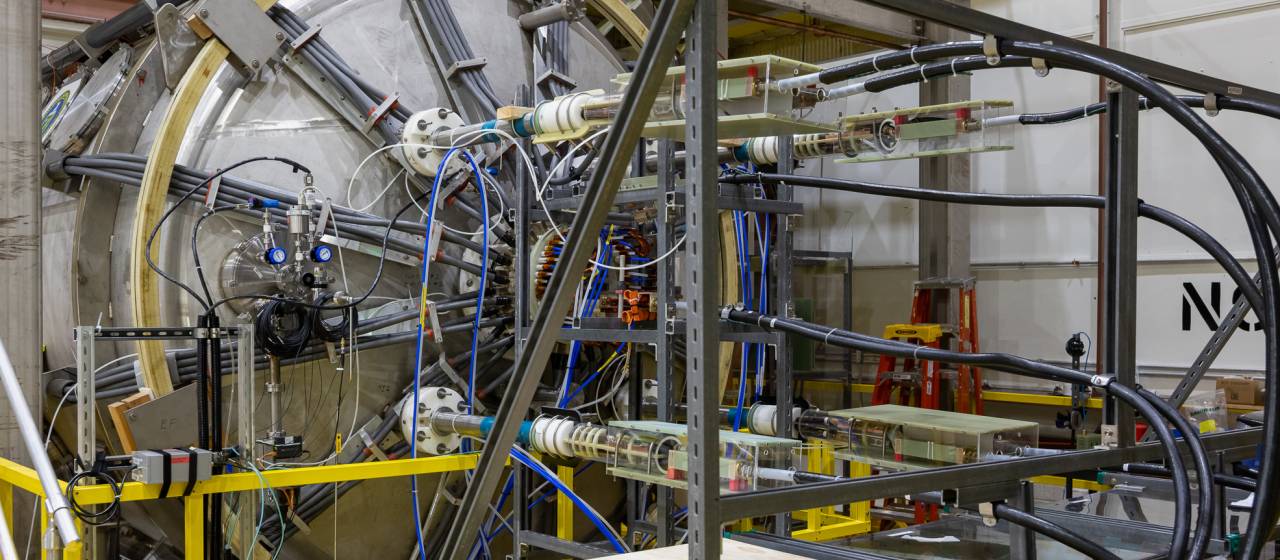

- Unprecedented new device at PPPL will help unravel mysteries of the universe

- Beth Lew-Williams Named 2025 Dan David Prize winner

- Senior Thesis Spotlight: What isotopes in redwood leaves reveal about dinosaur diets

- Senior Thesis Spotlight: A concerto inspired by history, art and the 'rough edges of Rush'

- Senior Thesis Spotlight: A ‘high-risk, but well-defined’ idea to advance quantum computing

- Princeton Summer Theater opens its 2025 season