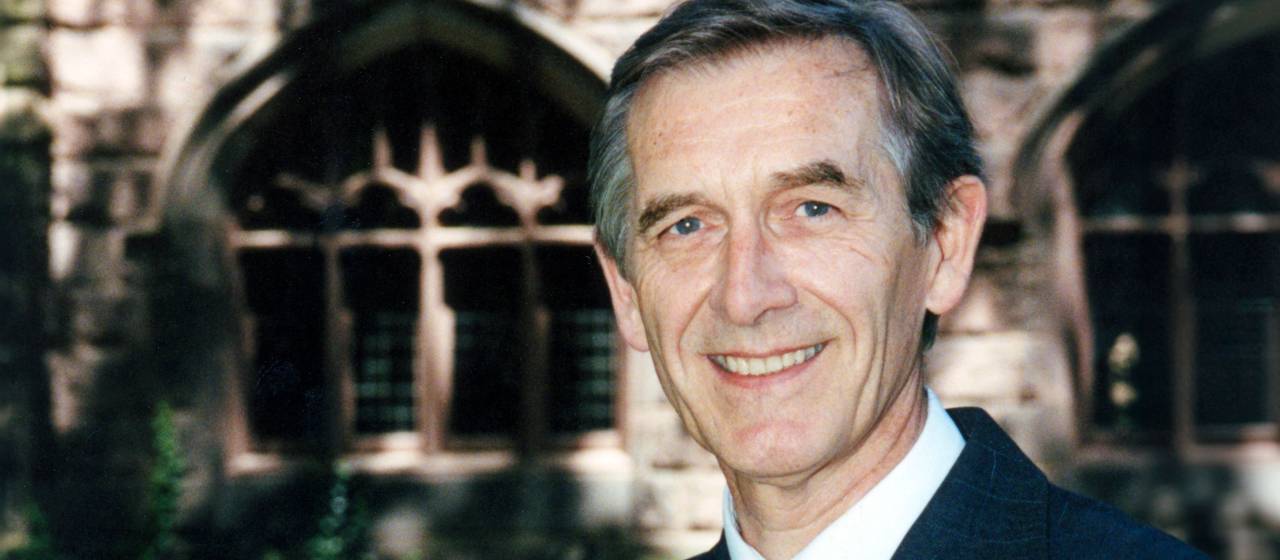

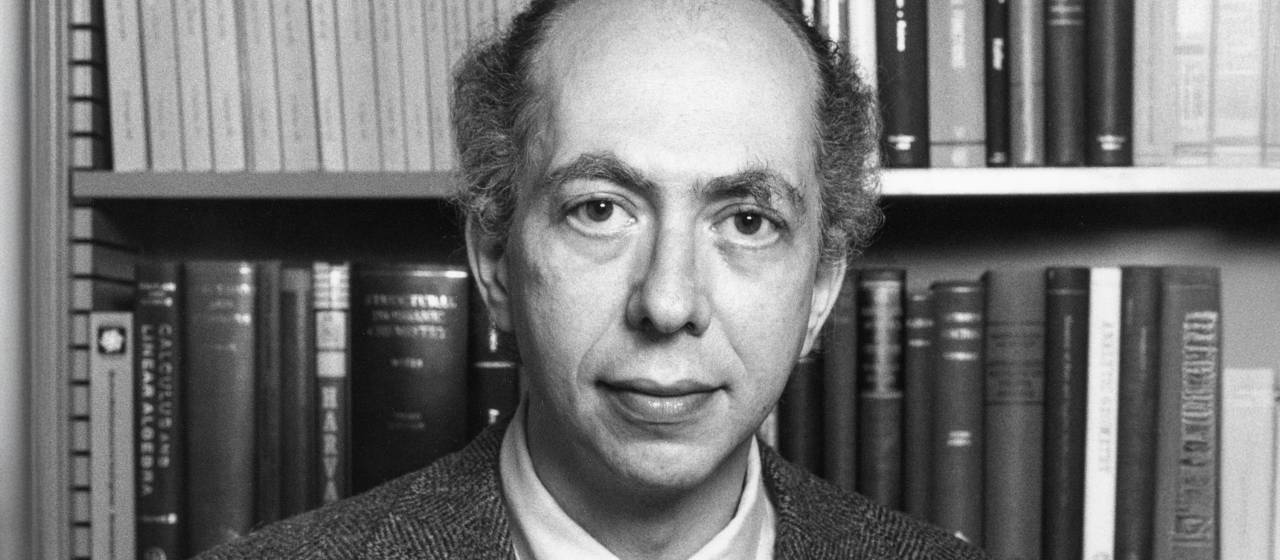

Erik Vanmarcke, leader in structural safety and wellspring of scholarly inspiration, dies at 83

Erik Vanmarcke, an emeritus professor of civil and environmental engineering and a pioneer in structural safety, died on July 7 at 83.

Erik Vanmarke

Through a better understanding of how forces like earthquakes and waves interact with buildings and bridges, Vanmarcke transformed the fields of structural reliability and risk assessment.

In 1983, while a faculty member at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), he published a foundational book, “Random Fields: Analysis and Synthesis.” The book introduces the mathematics of random fields — a way to represent properties that vary in space and time such as water levels and pressure fluctuations.

Vanmarcke’s research and consulting work spanned an extraordinary range of topics, said Princeton’s Ning Lin, a professor of civil and environmental engineering who earned her Ph.D. at Princeton in 2010 with Vanmarcke as her adviser.

In addition to seismic activity, soil properties and ocean waves, Vanmarcke explored how random field theory could be applied to describe energy density fluctuations in the very early universe, said Lin. In 1997 he published the book “Quantum Origins of Cosmic Structure,” and continued to work in this area until his death.

“He was very excited about applying the mathematical framework of random fields to something that’s quite grand,” said Lin. “His work on cosmology is far beyond my imagination, but his scholarly pursuit of science was very inspiring.”

“His pioneering work on earthquake occurrence models along faults significantly advanced the field and laid the foundation for many seismic hazard applications worldwide,” said Anne Kiremidjian, a former director of the John A. Blume Earthquake Engineering Center at Stanford.

Colleagues recalled Vanmarcke’s wisdom and generosity, particularly toward graduate students and junior researchers. “He had a way of listening and asking questions that helped steer others in fruitful directions while stimulating their own learning and creativity,” said Lin.

“Even after retiring he would often come to department seminars and events. I remember him sitting in some of my own presentations,” said Adam Hatzikyriakou, a vice president at the reinsurance firm SwissRe and Lin’s former Ph.D. student. “His questions always went to the heart of the issue but were always asked in an encouraging way. His support helped me immensely as I was beginning my graduate research.”

After moving to Princeton from MIT in 1985, Vanmarcke continued to advance the use of random field theory in engineering and published numerous studies on quantifying earthquake dynamics and designing for seismic safety. He traveled to countries including Turkey and the Soviet Union for earthquake engineering workshops. Later, he collaborated closely with engineers in China and organized summer schools for young researchers at Chinese universities.

He had a “global perspective and intellectual openness that defined [his] very being as a scholar,” said Zhaohui (Ann) Chen, who worked with Vanmarcke as a visiting scholar at Princeton from 2004 to 2006.

When Lin arrived at Princeton in 2005 to begin her graduate work, she had a strong interest in modeling wind hazards and hurricanes, which was a departure from Vanmarcke’s research areas, but he fully supported her in following her passions.

“His openness to thinking about fundamental connections between different natural phenomena really opened my mind,” said Lin. “I have my interest in hurricanes, but I also work on other hazards and related features. Never do I need to be bound by a certain research direction, because he taught me that I can explore without worrying about boundaries.”

When she returned to Princeton as a faculty member, Lin said, the transition from being Vanmarcke’s student to his colleague was seamless. “I didn’t feel much difference with Erik because he treated me as a colleague even when I was a student. He always wanted to have a conversation about an issue rather than telling me what was right or wrong,” she said.

Erik Vanmarke

“Unlocking the world’s essence”

Vanmarcke was “immediately hired” as a professor at MIT upon completing his Ph.D. there in 1970 “due to his intellect and brilliance,” said Ross Corotis, who finished his Ph.D. a year later. Both were mentored by the eminent earthquake engineer C. Allin Cornell.

Vanmarcke’s “Random Fields” book and other publications “completely redefined the field” of geotechnical engineering — a broad area that encompasses earthquake engineering as well as other interactions between structures and soil and rock, Corotis said.

“It took a few decades before the practice and research in geotechnical engineering could fully grasp what Erik had given them, and I think he now fully deserves to be called the father of geotechnical reliability analysis,” said Corotis, an emeritus professor at the University of Colorado-Boulder.

One of Vanmarcke’s great insights was to expand the probability frameworks that Cornell had used in designing structures. Vanmarcke applied these tools to the full continuum of materials that interact with a structure.

“But the problem was even harder there, because one is dealing with a three-dimensional continuum of material, material for which we often only have property values at a few discrete points,” said Corotis. “The problem then is one of not just random variables, but a whole three-dimensional space of uncertainties; hence the term random fields.”

In the textbook, “Erik revealed how uncertainty transcends mathematics to become a key for unlocking the world's essence,” said Chen. She noted that the book opens with a quote from an 1841 Ralph Waldo Emerson essay: “Nature is a mutable cloud, which is always and never the same.”

The book was expanded and republished in 2010, and Chen co-translated (with colleague Wen-Liang Fan) a Chinese version, published in 2017. While working on the translation, said Chen, “I was continually awestruck by [Vanmarcke’s] seamless fusion of rigorous scholarship, philosophical depth and humanistic vision — that signature style which everyone privileged to know Erik recognized as his indelible mark.”

In a profile of Vanmarcke in the May 11, 1987, issue of the Princeton Weekly Bulletin, he warned that engineers should take the risk of earthquakes on the U.S. East Coast more seriously — especially the risk they posed to nuclear power plants. “… the Earth’s crust is more fractured in the West, and the waves tend to lose their strength faster. In the East the [tectonic] plate is more nearly intact, and the waves that cause damage travel farther,” he said.

Over the course of his career, Vanmarcke served as a safety and risk management consultant to dozens of government and industry groups. While on the faculty at MIT, he served in the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy under President Jimmy Carter and was appointed to a dam safety review panel after the catastrophic failure of Idaho’s Teton Dam in 1976. He also evaluated wind damage risks for Boston’s John Hancock Tower, the tallest building in New England, and assessed levee safety in the Netherlands.

Beyond his contributions as an engineer, scholar and mentor, Vanmarcke was an avid reader, said Lin. He was conversant in five modern languages — his native Dutch as well as English, French, German and Spanish — and had studied Latin and ancient Greek in high school. (“We read Cicero like the newspaper,” he recalled in the Princeton Weekly Bulletin story.) When Vanmarcke retired, Lin said, he passed along a “wall of books” that still graces her office.

Lin talked with and visited Vanmarcke frequently after his retirement. “Every time I asked him how he was doing, he was not telling me he went on vacation or anything like that,” she said. “He was telling me he was doing some interesting research and reading. That is the kind of scholar and person he was.”

Vanmarcke was born on Aug. 6, 1941, in Menen, Belgium. He earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Leuven and a master’s degree from the University of Delaware. After completing his Ph.D. in civil engineering at MIT in 1970, he joined the MIT faculty until 1985, when he moved to Princeton. He transferred to emeritus status in 2013.

Among his many honors, Vanmarcke was elected a foreign member of the Royal Academies for Science and the Arts of Belgium, and a distinguished member of the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE). The ASCE also recognized him with its Alfred M. Freudenthal Medal and Raymond C. Reese and Walter L. Huber Research Prizes. He was the founding editor of the international journal Structural Safety.

Vanmarcke is survived by his wife, Lynne Durkee; three children and their spouses, Lieven and Manisha Vanmarcke, Anneke and Edward Forzani, and Kristien and Damon Webber; eight grandchildren; three step-daughters; and five sisters, Frieda Vanmarcke-Van Belle, Rosa Vanmarcke-Gilissen, Hilde Vanmarcke-Schoonjans, Christa Vanmarcke-Verhaeghe and Gerda Vanmarcke-Cauwenberghs, and their families.

Contributions in his memory may be made to the Institute for Advanced Study.

View or share comments on a memorial page intended to honor Vanmarcke’s life and legacy.