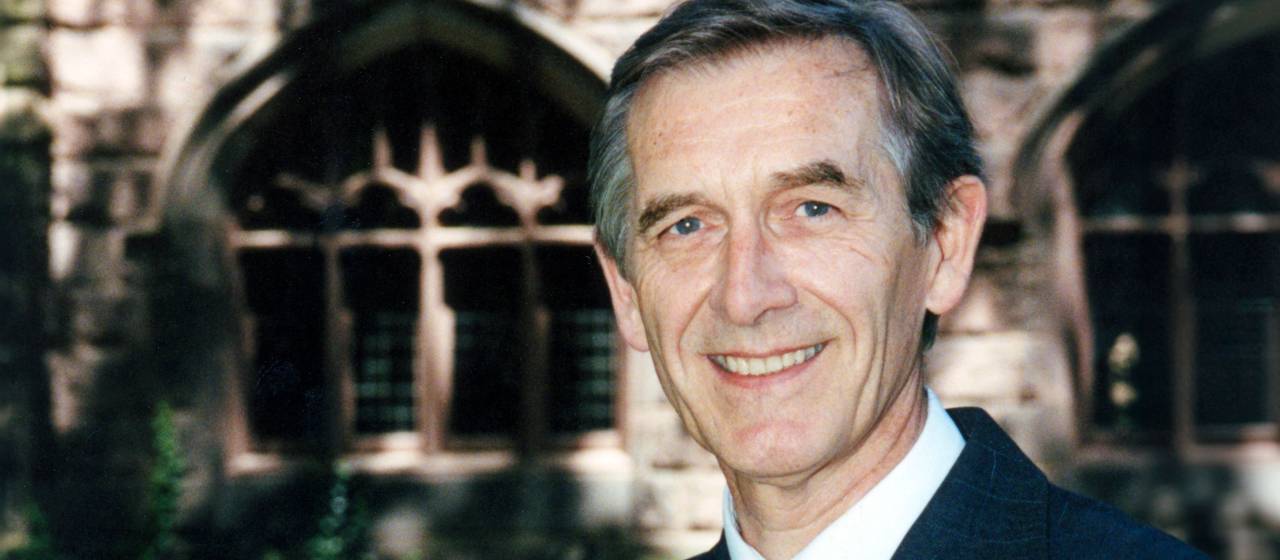

Class of 2025 Commencement address by President Eisgruber: 'A Fierce Independence of Mind'

May 27, 2025

— As delivered —

In a few minutes, all of you will walk out of this stadium as newly minted graduates of this University. Before you do, however, long-standing tradition permits the University president to offer a few remarks about the path that lies ahead.

As I began drafting this year’s speech, I found myself reflecting on what I recall from my own graduation — which, alas, is very little: after more than forty years, the day is mostly a blur.

I do remember leaving campus with a new, hard-shell Samsonite briefcase, a gift from my beloved grandmother, intended to mark my transition from backpack-toting undergraduate to office-going adult.

The briefcase would soon yield again to the backpacks that I favored for most of my professorial career.

During that post-graduation summer, though, I proudly carried my books and papers in the briefcase, feeling suitably professional and accomplished. One of the books I was reading at the time, on the recommendation of a Princeton mentor, was Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America.

The book, but not the briefcase, accompanied me to England where I began my graduate studies. Living outside the United States for the first time since my childhood, I marveled at the 19th century Frenchman’s ability to make perceptive and durable observations about a culture different from his own.

Tocqueville admired some of what he saw during his visits to America in the 1830s, but he was deeply skeptical about the country’s ability to produce humanistic and scientific achievements of the kind that distinguish this University.

For example, he reported that “there is almost no one in the United States who gives himself over to the essentially theoretical and abstract portion of human knowledge.”[1]

He opined that the United States “still does not have a literature, properly speaking,” and he predicted a future dominated by books that could be “procured without trouble” and “quickly read.”[2]

Tocqueville, despite all his truly magnificent insights, did not anticipate the rise of universities like the one from which you graduate today.

He did note that Americans had a “very high and often much exaggerated idea of human reason” and were prone to “conclude that everything in the world is explicable and that nothing exceeds the bounds of intelligence.”[3]

Tocqueville also observed that Americans “constantly unite,” forming organizations and associations “to give fetes, … found seminaries, … build inns, … raise churches, … distribute books [and] create hospitals, prisons, [and] schools.”[4]

If Tocqueville had put together these observations—about Americans’ zealous faith in reason and their incessant associative activity—he might perhaps have predicted the network of research universities that we know today.

Be that as it may, America’s colleges and universities have changed the country for the better. The nation that Tocqueville thought ill-suited to the “theoretical and abstract portion of human knowledge” has become a magnet for the world’s leading mathematicians and scientists.[5]

The country that Tocqueville thought might never produce a literature of its own now cultivates brilliant writers and critics not only at this university but at many others, including, for example, at the famous University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

Tocqueville wrote that “there is no country in the civilized world where [people] are less occupied with philosophy than the United States,” but New Jersey by itself boasts two of the world’s greatest philosophy departments, at Princeton and Rutgers.[6]

Yet, if Tocqueville did not foresee the rise of America’s universities, his observations about democratic sentiments should alert us to a persistent tension between our scholarly institutions and the broader society upon which they depend.

The creativity that universities cultivate, the idiosyncrasies that we tolerate, and the speculative or esoteric research that we cherish: all of these can put universities at odds with the more pragmatic culture around us and thereby jeopardize the academic freedom on which our institutions vitally depend.

Tensions between the academy, public opinion, and government policy have ebbed and flowed over the course of American history. They are now at an unprecedented high point.

In this tender and pivotal moment, we must stand boldly for the freedoms and principles that define this and other great universities.

We must also, at the same time, find ways to listen to thoughtful critics and steward our relationship with the broader society upon which we depend.

Universities risk losing public support if they deviate from their core mission of teaching and research, or if they appear to become organs of partisan advocacy rather than impartial forums for the pursuit of truth and the dissemination of knowledge.

People sometimes make this point by recommending that universities adopt a posture of “institutional neutrality,” a concept that they take from a report issued in 1967 by the Kalven Committee at the University of Chicago.

Though I agree with much that is said in the Kalven Report, I have never liked the language of “neutrality,” partly because “neutral” has multiple meanings.

“Neutral” can mean “impartial,” which is a more precise way to capture what the Kalven Committee had in mind.

Another meaning of “neutral,” however, is “lacking distinguishing quality or characteristics.”[7]

Synonyms for “neutral” include: “innocuous,” “unobjectionable,” “harmless,” “bland,” and “colorless.”

Some current-day proponents of the neutrality standard seem to relish the term’s double meaning. They want university faculties and students to produce useful inventions, illuminate poetic beauty, and study the virtues of successful leaders, but they appear to become uneasy when, for example, scholars expose and analyze the role of race, sexuality, or prejudice in society and politics.

The actual Kalven Committee was under no such illusion. It described universities this way:

“A university faithful to its mission will provide enduring challenges to social values, policies, practices, and institutions. By design and by effect, [a university] creates discontent with the existing social arrangements and proposes new ones. In brief, a good university, like Socrates, will be upsetting.”[8]

Like Socrates! The reference is telling. As the Kalven Committee certainly knew, Socrates was so upsetting—so colorful, so provocative, so decidedly not neutral—that the Athenians sentenced him to death for disrespecting their most sacred beliefs.

Universities might be less vulnerable to criticism and attack if they were bland, innocuous, and neutral—but then they would not be true universities.

Great universities must have a Socratic spirit.

We aim to encourage and elevate what Tocqueville depicted as the sometimes irritating tendency of Americans, and democratic citizens more generally, to believe that human intelligence can explain, critique, and improve the world.

At the heart of Princeton’s undergraduate and graduate degree programs is a commitment to inculcate a fierce independence of mind. We want you to have the skill and the courage to ask questions that are unsettling and uncomfortable to the world, and, indeed, to you.

I hope you have embraced this independence during your time here, and that you have also learned how to speak up for what you believe even when it may be uncomfortable to do so.

I hope, too, that these habits will stay with you as you venture forth into a world that needs your creativity, your learning, and your valor.

The paths that you follow from this stadium today lead into a world more fraught, turbulent, and uncertain than the one that I entered with my brand-new briefcase four decades ago. Yet, whether you depart carrying backpacks or briefcases or neither of the two, you should know, as my classmates and I did, that you will always be welcome back on this campus.

Indeed, all of us on this platform hope that you will return often to Old Nassau. We will greet you then as we cheer you today, wishing you every success as Princeton University’s Great Class of 2025! Congratulations!

[1] Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, trans. and ed. Harvey C. Mansfield and Delba Winthrop (University of Chicago Press, 2000), 434.

[2] Id. at 446, 448.

[3] Id. at 408, 404.

[4] Id. at 489.

[5] Id. at 434.

[6] Id. at 403.

[7] “Neutral,” in vocabulary.com, accessed May 22, 2025, https://www.vocabulary.com/dictionary/neutral.

[8] Kalven Committee, Report on the University’s Role in Political and Social Action (University of Chicago, November 11, 1967), https://provost.uchicago.eduhttps://www.princeton.edu/sites/default/files/documents/reports/KalvenRprt_0.pdf.